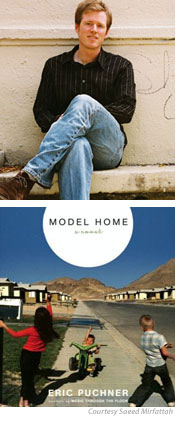

It took four years, after a first draft weighing in at more than 800 pages, before CMC Assistant Professor of Literature Eric Puchner was finally satisfied with his novel, Model Home: A Novel.

"I did a lot of rewriting and killed a lot of darlings," he says. But the effort was worth it.

Model Home delivers penetrating insights into the American family and into the imperfect ways we try to connect, from a writer "uncannily in tune with the heartbreak and absurdity of domestic life," (Los Angeles Times).

It took four years, after a first draft weighing in at more than 800 pages, before CMC Assistant Professor of Literature Eric Puchner was finally satisfied with his novel, Model Home: A Novel.

"I did a lot of rewriting and killed a lot of darlings," he says. But the effort was worth it.

Model Home delivers penetrating insights into the American family and into the imperfect ways we try to connect, from a writer "uncannily in tune with the heartbreak and absurdity of domestic life," (Los Angeles Times).

Puchner says the idea for Model Home occurred to him while he was finishing his collection of short stories, Music Through the Floor.

"I wanted to write something about my late father, who lost all his money when I was a teenager and ended up living in the Utah desert, a casualty of the American dream," he explains. "But up until then my attempts at approaching his life directly hadn't worked out. So I took a big step back and came up with the Zillers, a family that bears no relation to my own, and was able to write much more convincingly, and empathetically, about my father's plight."

Along the way, Puchner says, he became increasingly interested in the lives of the other characters he'd created, so much so, he says, that the children in some ways end up hijacking the book.

"Somewhere in the back of my mind, too, was a true story a friend of mine had told me, about a man who came home from vacation one day and lit a cigarette before opening his front door, and his house exploded," says the CMC professor. "It was such a potent, disturbing imageso haunting in its suddenness, in what it says about the precariousness of homethat I couldn't get it out of my head."

Puchner cautions readers not to read too much autobiography into his novel.

"I was a teenager in Southern California in the eighties, and we were downwardly mobile in something of the same way that the Zillers are," he says. "But everything that happens is utterly fictional. The characters are completely made up and bear absolutely no relation to my family (thank god). I do feel it's in some ways a book about my father and about my own youth but it's an emotional echo, not a literal one."

***

How does the novel compliment or intersect with your own interests and what you want to say?

EP: I am fascinated by California, and a lot of my fiction seems to be about how we've succeeded or failed to live up to the dream of the West. I suppose I'm something of a regional writer, in that respect. Part of what the novel's about is the phenomenon of the gated community, and how the rise of the exurbs has shaped our landscape and our sense of community and the great geographical and ideological schism that's occurred between where we sleep and where we earn our livings. I'm particularly interested in the exurbs outside of L.A. the fact that so many people have voluntarily moved to the desert, to which they're not ecologically suited, content to spend half their lives on the freeway in order to have a larger home. The subculture of desert subdivisions, with their verdant, New England-y sounding namesGreen Valley Springs, Gulls Landingfascinates me. Ernest Hemingway used to set a goal of writing around 500 words a day. What goal, ritual or routine works best for you when you are immersed writing?

EP: I don't use word limits, though I know that works for some writers. For me it's all about ritual: being there in front of my computer as much as possible, making myself visible so that inspiration can find me. I listen to Bach's cello suites over and over. My wife, Katharine Noel, who also teaches at CMC, listens to loud indie rock while she writes, so we sometimes have stereo wars.

Who are some of your favorite writers?

EP: I have too many favorites to list here, but I'll say that no book moves me quite like Anna Karenina. There's a scene in Model Home where Lyle, the Zillers' daughter, thinks about how when she puts down a great book the world often seems "less real than the one she'd been reading about . . . as if God had decided to phone it in." That's how I feel when I read Tolstoy.

Many of the writers I admire are ones that marry the comic and tragic in some way: Nabokov, Lorrie Moore, Aleksandar Hemon. Comedy and despair come from the same place for me, and I'm interested in mining that place in my work. Do you own a Kindle and what do you think about virtual devices replacing the tactile feel of real books?

EP: I don't own a Kindle, no. I'm not particularly worried about the longevity of the book. People will always crave that physical connection with the page, I think, that literal feeling of opening a world and stepping inside. It seems to me that the book is a perfect invention. But of course, I'm from a generation for whom books still hold a sort of totemic power. Maybe that time is passing.

What's next for you?

EP: I've been working on short stories again, my first love, so we'll have to see where they lead. And I've always got the germ of a novel in my head. I like to have a balanced diet in my writing life.