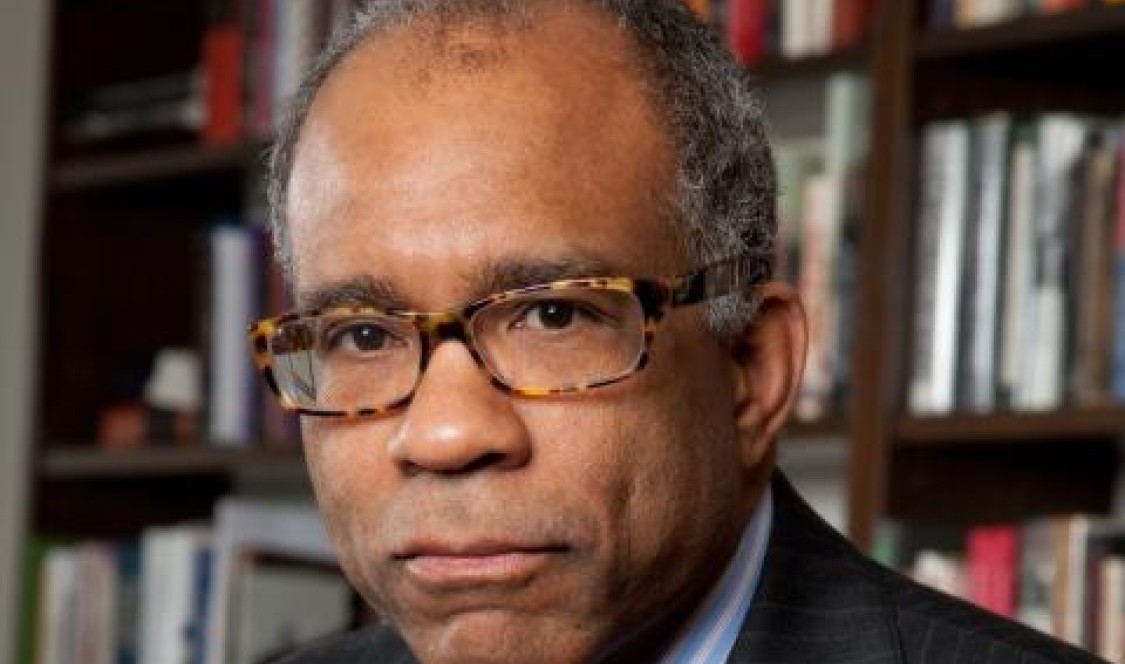

Randall Kennedy, the Michael R. Klein Professor at Harvard Law School, wanted input from attendees of his Marion Miner Cook Athenaeum talk (“The Race Line in American Life”) last Wednesday.

The project for which he solicited input stems from Martin Luther King Jr.’s last public speech; the famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech he gave on April 3, 1968, the day before he was assassinated.

Prof. Kennedy quoted Dr. King’s “I’ve been to the promised land” line from that speech but said that what King omitted was any mention of what the “Promised Land” looked like.

“Where are its boundaries, its topography, its key landmarks?” Kennedy asked.

According to Kennedy, almost from the instant King finished his speech, there has been a continuous discussion about various aspects about the American race question. “There has been lots of writing, lots of talking,” he said, “but this question of what the racial Promised Land looks like and what we should be seeking to create seems to me to be a question that has not gotten the attention that it warrants. Racial justice, racial equality, racial decency are abstractions.”

Kennedy has spent a career canvassing the many ways in which racial lines have been drawn overtly and, covertly, self-consciously and unconsciously in American life. At his alma mater, Harvard, he teaches courses on contracts, criminal law, and the regulation of race relations and his appearance at the Ath was co-sponsored by the President's Leadership Fund.

Kennedy said that among the prevailing conceptions of the “Racial Promised Land,” one predominates – the idea of a race-blind America.

“I would bet that if you went out and asked people what is the sort of society in racial terms that we should be seeking to create, I think a lot of people would say an America that is race-blind,” he said. “That idea has real virtues to it. One virtue is that it does represent a clear break from an awful past practice. It is certainly a repudiation of ‘pigmentocracy.’ And that’s a good thing. You are repudiating racial slavery, segregation, white supremacy. A second good thing is it does show a healthy skepticism regarding the ability of individuals and institutions to distinguish between various sorts of racial distinctions.”

It is a measure of how far we’ve come in dealing with race that we now sneer at the very thought of segregation and that it could ever have been seen as consistent with equal protection under the law.

“A lot of smart people thought that – Oliver Wendall Holmes, Justice Cardoza did,” Kennedy said. “It wasn’t until 1954, the year that I was born, that the Supreme Court got around to saying vis-a-vis public schooling, that segregation was inconsistent with the Equal Protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.”

A third virtue of the “race-blind America” idea, Kennedy said, is that it has a nice clarity to it, “the bumper sticker advantage.”

But challenges come with every perceived advantage. A vigorous effort to extinguish race-minded decision-making, in Kennedy’s view, would entail a level of intrusiveness on privacy and freedom of association that many people would find intolerable.

“It would entail the destruction of racial refuges, identities and affinity groups like ones you find on college campuses,” Kennedy said. “If you were totally committed to the idea of a race-blind America, what would be the status of those affinity groups?”

Kennedy posited that some people might favor race-blind Constitutionalism that would come into play in public but not private matters.

“One real big problem with color-blind Constitutionalism is that when you really push it, no one’s really for it,” he said. “Two leading proponents are Supreme Court Justices Scalia and Thomas, but even they would hedge when faced with the question of whether the federal government should never, ever take race into account. They are careful to put an exception in there.”

One alternative conception of a race-blind America, Kennedy explored, was from the perspective of America as a racial salad, a mosaic or an orchestra featuring different instruments (horns, woodwinds, etc.).

“It’s a powerful metaphor,” he said. “The idea of having institutions that ‘look like America.’ It’s become a very powerful, normative theme, but if you deviate from it – big problems ensue.

“I think there are various virtues to the ‘look like America’ theme,” Kennedy continued. “There is the idea that things that look like America, will be better because various groups have special capacities, insights, experiences. And it provides a validation and protection of group identity.”

But the problems with this motif, according to Kennedy, are regarding what specific groups will constitute the parts of the salad.

“There is no text that gives a good answer to the text that I have proposed,” he said. “I think that the question I have posed is a real question, a daunting question and a question that will require a lot more thought and it’s a question that I’m certainly trying to attend to.”

In the brief Q&A that followed Kennedy’s presentation, one student asked what Kennedy thought about the flurry of on-campus activism regarding perceived racial bias that has affected many U.S. campuses in the last few months.

Kennedy mentioned that Princeton students want to rename the university’s Woodrow Wilson School as a reaction to Wilson’s segregationist stance in the federal government.

“Woodrow Wilson was a white supremacist. He had retrograde racial ideas. His policies were very hurtful to many Americans,” Kennedy said. “I commend the students for blowing the whistle on this. I think complacency with respect to this. However, the issue of what should happen is a complicated matter. I think I’m in favor of a regime of addition rather than subtraction. I think I’m in favor of keeping what exists for a variety of reasons including the protection of memory.”

Kennedy added that he would also favor Princeton recognizing individuals that have done wonderful things in American life but who have not received the attention and valorization that their efforts warrant.

“Students have focused attention on the compositions of curriculums and faculties. I think all these things need to be thought about and it’s dissonant students that have prompted this attention,” Kennedy said. “But that is not to say that I have agreed with everything that dissonant students have done and said. I’m actually quite critical of some of the positions and some of the strategies taken of students who protest.”

In Kennedy’s view, every institution in America has gender or racial problems and it’s important to distinguish between a problem and something that is characteristic of the institution.

“In many of our institutions of higher education, what is the prevailing ethos?” Kennedy asked. “It is an ethos of thoughtfulness, of self-criticism, of debate, of learning, the elevation of knowledge, the valorization of knowledge. Those things are very useful and precious and I think we ought to be very careful in what we do and say about our institutions of higher learning, particularly in a world that is so full of people who are fully prepared to destroy institutions like CMC or like mine. While you want to push institutions of higher education, while you do want to shine a light on their complacencies, you must also recognize how precious and fragile they are and how important they are.”

Kennedy attended Princeton University, Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, and Yale Law School. He clerked for Judge J. Skelly Wright of the United States Court of Appeals and Justice Thurgood Marshall of the U.S. Supreme Court. Awarded the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award for Race, Crime, and the Law (1997) in 1998, Kennedy writes and speaks on a wide range of topics. His books include For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law (2013), The Persistence of the Color Line: Racial Politics and the Obama Presidency (2011), Sellout: The Politics of Racial Betrayal (2008), Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity, and Adoption (2003), and Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word (2002).

##