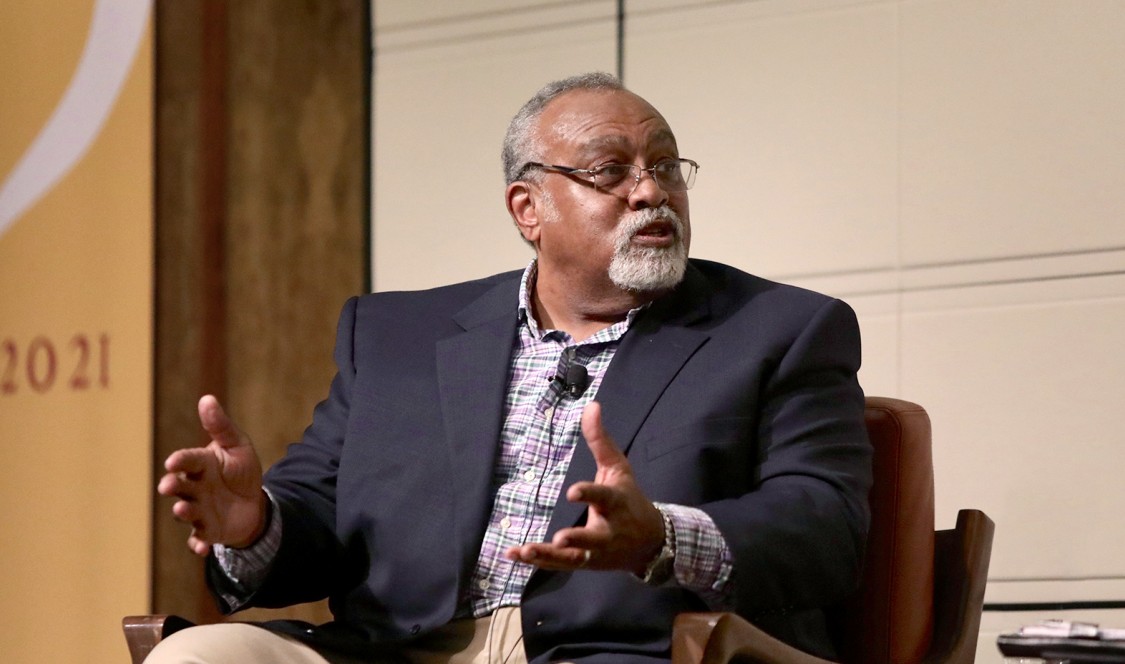

Brown University economist and noted heterodox thinker Glenn Loury recently sat down with associate professor of government Michael Fortner in a conversation on “Race and Commerce: The American Experience.”

Just contemplating the evening’s theme left Fortner unsettled, he confided at the start of the Athenaeum discussion, which was part of CMC’s 75th Anniversary Distinguished Speakers series.

“As the young people today say: ‘I was shook.’ Because the first thing that came to my mind was that my ancestors were commerce,” Fortner said. “They were sold, they were bought, they were traded.”

Referencing the exhaustive work of Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson in his 1982 book, Slavery and Social Death, Loury, who is the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences and Professor of Economics at Brown University, noted that enslavement isn’t unique to America or the West. It traces back to antiquity and was practiced worldwide.

The Atlantic slave trade, in particular, couldn’t have happened without multiracial collaboration.

“There’s a lot of blame to go around,” Loury said. “Slavery begins with the capture of Africans who were enslaved by other Africans in Africa. Europeans did not pull that off by themselves.”

Loury further referenced Fortner’s earlier comment about his ancestors being commerce. “But slaves were only some of your ancestors. They were only some of mine. My name is Loury. I’ve got Scotch-Irish ancestors.”

Educated at Northwestern University and MIT, Loury is a widely published authority on applied microeconomic theory, game theory, and the economics of racial inequality. In 1982, he became the first Black tenured professor of economics at Harvard. Since 2005, he has been on the faculty of Brown University.

Asked by Fortner why so many corporations and elite institutions have embraced anti-racism principles, Loury pointed to incentives relating to brand preservation and market forces, the logic of administrative development, a desire to cater to important stakeholders and constituencies.

The problem, Loury worries, is that while each institution “may be doing what’s good for itself, the net effect may be to avoid addressing the root causes of racial disparity.”

Not only does Loury find anti-racism, “as a way of talking about the conditions of African Americans, patronizing in the extreme,” it’s counterproductive.

“Equity won’t get you equality of standing,” Loury said. “It won’t get you equality of respect. It will not give you mastery. Instead, you become a ward. You become a client. Your position is ‘by their leave.’ It’s because they feel sorry for you, it’s because they feel guilty. That is not equality.

“Here’s my bottom line: we can lose ourselves in this pipe-dream narrative, but the 21st century is not going to wait for anybody. While we are going around with our hand out, talking about what was done to our ancestors, people are busy building businesses, building families, building homes, and creating their lives. They’re not going to stand still for us.

No one said life was fair. I think we better get busy making the best of it right now.”

It’s not a popular message, Loury acknowledged: “I wouldn’t run for Congress on that speech. But I run my family on that speech. That’s what I tell my kids.”

During the question and answer session, students posed thoughtful, original questions.

“If race is a social construct,” asked one senior, “is it really necessary? Should we abolish it?”

A first-year student wanted to know Loury’s opinion of indirect reparations to Black communities.

One student wanted to hear Loury’s thoughts on the push for near-universal college education in light of low graduation rates among young people from underserved communities who might be better served by vocational training. Another student asked Loury to draw an ethical line between justifiable profiling and unfair stereotyping. Loury’s thoughtful responses drew on a wide circle of authorities, among them Robert Cherry, Thomas Chatterton Williams, and Robert Nozick.

Loury ended on a positive note.

Noting major demographic changes he’d witnessed in his lifetime, Loury said: “It’s a new world. Interracial marriage is up, biracial kids are up, identity is fluid. Why would we lock ourselves into the 19th century? We have to allow freedom for people to explore the fullness of our humanity. I’m Black, but I’m not only Black. My kids are Black, but they’re not only Black. We don’t need to go home. We need to look ahead.”