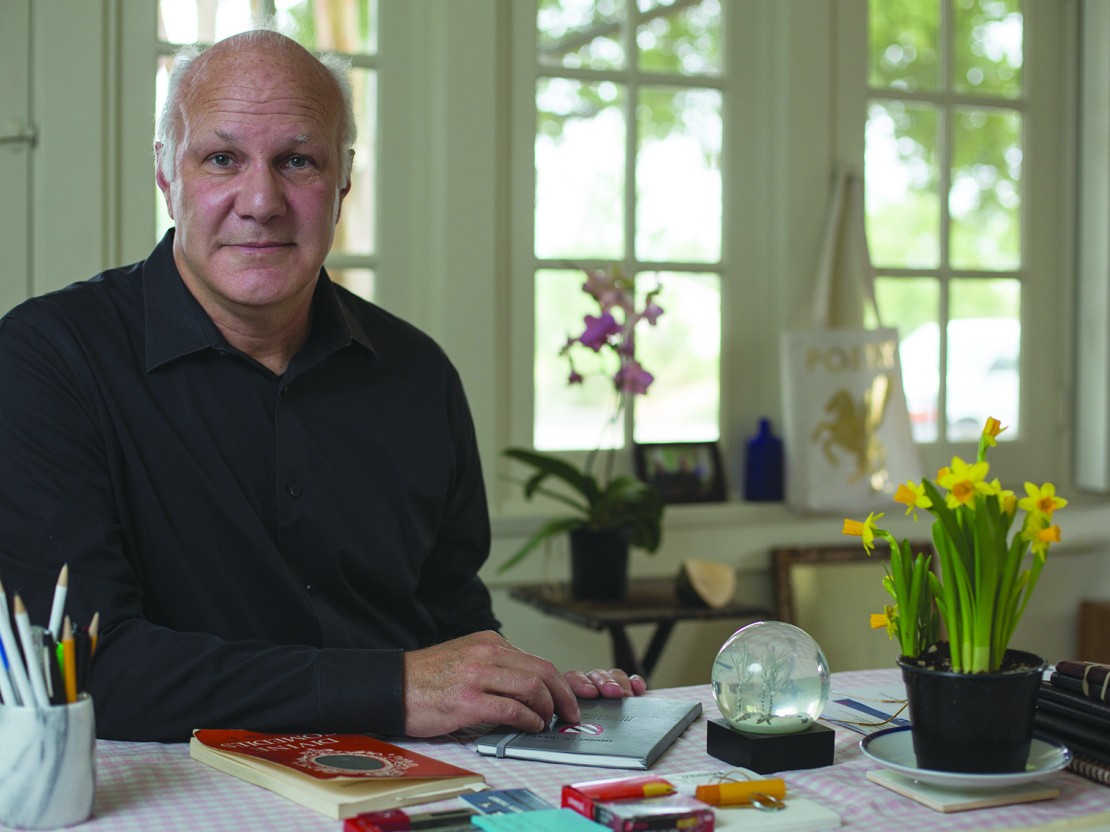

The poet Henri Cole spends his life immersed in language. Still, he doesn’t quite trust what words do to us.

“There’s a lot of poetry that’s not about fear, grief, despair, triumph,” he says in a gentle Southern accent. “It’s more about the dance of language. But that’s not the kind of poet I want to be. I want to be a bit about the dance of language—but with emotion as well.”

Cole sees his nine books as “a record of one single movement away from the big orchestration of language and elegance.”

For all his efforts to get at something deeper—to get to fear, grief, and the rest—Cole is no slouch when it comes to surface effects. Some of his poems are like a gallery of imagery: he writes with almost photographic precision about the way people keep their homes, and equally vividly about animals and plants. He’s hardly a decorative poet, though. The voice that speaks in his poems often seems to come from a fraught, deeply curious—sometimes wounded—figure roaming the world, looking for meaning. It makes his work simultaneously light and dark.

Cole is also very hard to place. He’s lived in Japan, Italy, France, Germany, Oregon, Western Massachusetts, and Boston: He seems like a latter-day exile or émigré, someone at home everywhere but bringing memories, painful and rapturous, everywhere he goes. Even a stint delivering flowers as a young man in Tidewater Virginia gave him a sense of beauty and pain.

Cole, who came to Claremont McKenna in the fall, is not just a wandering lyricist: He’s one of the best-regarded poets alive. “It has been apparent for some time that Cole is the most important American poet under sixty,” William Logan, a critic who rarely offers easy praise, wrote last year in The New Criterion. “His late work has made the bland, generic poems of so many of his generation an embarrassment.”

Rather than boast, though, or adopt an arrogant manner to match his literary reputation, Cole speaks calmly and cautiously. When making simple statements, he sometimes sounds as if he were asking a favor. He’s friendly, curious, and reticent in conversation: You can speak to him for an hour and learn more about yourself than about him.

***

“When I am writing, there is no pleasure in revealing the facts of my life,” he told The Paris Review. “Pleasure comes from the art making impulse, from assembling language into art.” The facts of his life, though, help decipher his work. Even in childhood, Cole was a complex blend of influences. He grew up under the shadow of both the military and the Catholic Church, and he was raised mostly in Virginia despite being born in Japan and bearing a French name.

His father came from North Carolina sharecropping people, and enlisted in the Air Force; he loved reading, including the encyclopedia. Cole’s mother was ethnically Armenian, hailed from Marseilles, and seems to haunt many of his poems whether she’s named or not.

The poems about Cole’s parents—who eventually split up—are some of his most vivid: He describes his mother’s “tweezered suburbs,” his father living in a “dirty-dish mausoleum.” He writes about them with a complex blend of emotions.

“I think about my parents all the time,” sighs Cole. “I probably shouldn’t write about them so much, but I can’t stop thinking about them.” He writes in one of the poems: “After the death of my father, I locked/ myself in my room, bored and animal-like.”

Cole is not the kind of poet who only chronicles his own origins. Some of his best-regarded work comes from his time living in Japan – where he was born, and to which he returned in middle age -- and Rome, which led to a shift in his writing style. “Italy was about the archeological past and the art in the country. It was a template for exploring the self. I was raised in the church, so Italy was an interesting place for a non-practicing Catholic.” When he remembers the country, he thinks of its paintings: “saints, martyrs, Christ nailed to a cross.”

Whether he’s writing about a Japanese kimono, Italian art, a baby shark, or his father’s death, Cole aims for psychological complexity. And here we’re back to language and what it does to us, especially the way language can become artifice, a barrier. “I don’t want words to sever me from reality,” Cole wrote in the poem “Gravity and Center.” Nor does he want his verse to serve up easy consolation. Instead, as he told The Paris Review, a poem can be “an x-ray of the self in a moment of being, and that usually means dissonance.” He’s also compared his poetic voice to a needle going into the skin. Whatever the metaphor, the stakes for Cole’s poetry are high.

Since arriving at CMC at the start of the fall term, he’s taught writing, seminars on major Modernist poets, and helped bring Frank Bidart and Louise Glück to campus.

He taught at intellectually serious places—including Harvard, where he worked for seven years—and he says he’s impressed with CMC’s commitment to literary study. “There are five people here who do poetry,” he says. “There’s not even five people at Harvard who do poetry.”

Cole loves the quiet setting, the dry foliage, the proximity of the desert, his ability to bike around Claremont village. The placid quality of the area allows him to concentrate on writing and teaching, which he sees as serious business. He’s found that his students agree. Poetry, he says, “seems to be like a blood infusion or something.”

Whether they’re learning to read poetry or write it, his students are not just preparing for a career, but trying to deepen themselves.

“This is a place,” he says, “in which their being is involved in a slightly more risky way.”

A staff writer for Salon magazine, Timberg is the author of Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class.