My dad grew up in an enclave of southern and eastern European immigrants who crowded into the First Ward of Allentown, Pennsylvania. Work was easy to be had at the breweries where his father worked, or at Bethlehem Steel or Mack Trucks. Few kids went to college.

But he wrote well. He found work as a night copy boy at the Morning Call newspaper, where one New Year’s Eve he carried the news that Hank Williams had died. A friendly priest told him he was “college material.”

So, alone, my father boarded a bus and left Allentown for Northwestern University, intending a career as a reporter. There, he fell under the mentorship of Donald Torchiana, the scholar of English literature, and that changed his career path. At Northwestern he also met my mother, Lolly Brown, from a well-to-do family in Des Moines. They fell in love and married, though he had no money so she paid for the wedding ring.

They spent their first two years of married life in Europe on a Fulbright Scholarship, studying in Italy, France, and Germany. In 1959, they returned to the states with me, now five months old, and to Harvard, where he earned a Ph.D in comparative literature under Harry Levin, who introduced him to the Renaissance.

Claremont Men’s College hired him in 1963. We drove across the country in our beige Buick, with my dad telling me and my brother Nathanael stories of Odysseus along the way.

CMC became part of our childhood. We swam each summer at its pool. Watched dominant Stag basketball teams under CMC’s late, great Ted Ducey P’73. In my dad’s cluttered Bauer office, we helped him paginate his first book, The Renaissance Discovery of Time.

He loved the school, that he could encounter students everywhere. My dad admired Robert Kennedy, campaigned for him, and told me once of a waitress who said she wouldn’t vote for him because someone would kill him if he won. He woke me early that morning in June to watch as Frank Mankiewicz announced RFK’s death.

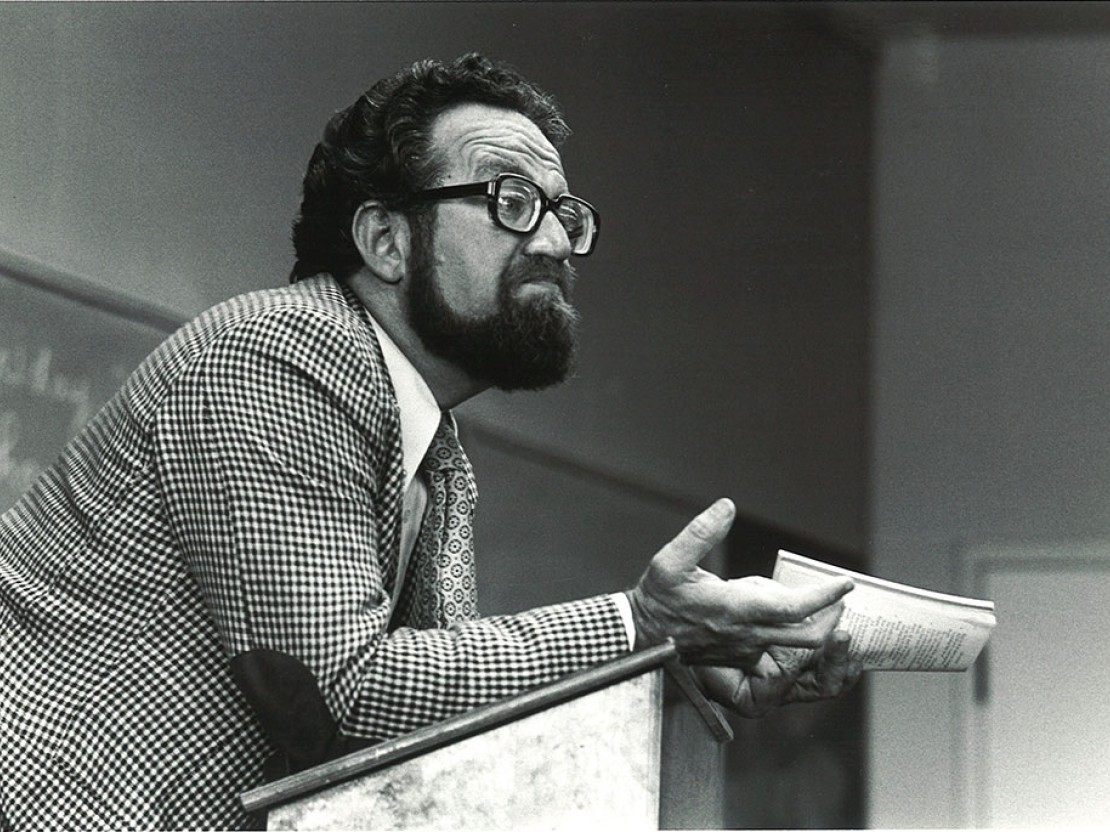

He protested the Vietnam War, and voted for George McGovern; his hair grew shaggy and his beard appeared. At a demonstration he took me to on the CMC track, I had a shirt stenciled with a clenched fist—something to do with the 1969 Student Moratorium. He once took my brother Ben to a sit-in, and he received a nasty letter from a colleague. Family friends were artists and poets. Dinner guests discussed Richard Wright and John Coltrane.

Yet the 1960s fit my dad, a child of Allentown’s traditionbound immigrant enclave, only part way. He was already over 30 and a father of four when the Summer of Love happened.

By the end of the 1970s, he was fading from the Democratic Party, which he believed had left him, though his favorite presidents remained Harry Truman and John Kennedy. He railed against what he saw as the stifling of discourse by conflating social activism with art and scholarship.

In 1979, I was away at UC Berkeley. My brother Nathanael had grown into a rebellious kid. One early morning, coming home on the Pomona Freeway from a party, Nathanael was in the passenger seat in a car with some friends. The driver fell asleep and slammed into a car parked by the highway. My brother died instantly, the only one hurt in the car.

My mother had bone cancer by then. She died three months later. They’re buried under a tree at Oak Park Cemetery.

This crushed my father. He had seen too much death too young. His mother and father had both died before he was 22. He now raised my two youngest brothers—Ben and Josh ’88—alone while I was away at college.

Without the influence of my mother, and his politics changing, so did his CMC friends. Chemistry professor Tony Fucaloro was over often. His CMC colleagues helped him navigate life during those years. Mike Meyers P’03. George Dunn ‘72. Bobby Trujillo ‘74. Mike Rothman ‘72. Colin Wright. Freddy Balitzer P’88 GP’21. Ed Haley. Charlie Lofgren. I’m missing a few.

They played basketball at the CMC gym, and a lot of poker, occasionally at the home of Randall Lewis ‘73 P’10 P’11 P’13. Some of them were involved in the Reagan campaign. When I returned home, dinner companions discussed Milton Friedman; I was given a book by Jeane Kirkpatrick for Christmas. My dad’s politics, though, were never strictly liberal or conservative. They were an amalgamation of ideas and values accumulated through life and literature, independent above all.

He met Roberta Johnson, a Kansas University professor of Spanish literature. They fell in love, married in 1998, and four years later, he retired. In retirement, even as Parkinson’s Disease slowly captured his body’s terrain, he was a dynamo. He wrote three books of literary criticism. He also produced five books of poetry, which tended toward storytelling.

Books were the only material possessions my dad loved. We had them everywhere and I came to believe a house without books is like a city without trees.

At his home, his shelves remain the earthly expression of his fertile mind. One of his favorite poets, Robert Frost, stands in between Joseph Stalin and Martin Luther. Henry Kissinger’s World Order next to Lord of the Flies. I hesitate to disrupt their placement, afraid that there was some system at work, but probably not. I think he enjoyed throwing ideas together and seeing what the collision produced.

On Christmas Eve, when our families were about to meet for dinner at my house, we thought it best he not come over but instead head to a hospital for his low blood pressure. It didn’t seem safe. But he insisted on being at the dinner. Marlon Batiller, his dearest caretaker, told him, “If you can stand, I’ll take you.” He stood. On this, his last family Christmas dinner, more fragile than ever at age 83, he read For the Union Dead by poet Robert Lowell.

A few weeks later, on his last time out of bed, my father asked Marlon to pull him up and into his wheelchair, and roll him into the dining room. There, on the table, sat the readings for his next project. It was to be a book about the 1800s. His reading for it included Treasure Island, Huckleberry Finn, biographies of U.S. Grant, Napoleon, and others.

That morning, emaciated, he sat in his wheelchair beside his books. He held the Grant biography. Then he leafed through the Napoleon. The books were new, and thick, and heavy. He re-read a bit from each.

Finally, he placed them back on the table and he sat in the chair in silence just looking at them one last time. And after a great long while, he asked his caretaker to wheel him down the hall and back to the bed, where, two days later, he died.

—Sam Quinones is the author of Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic